Learning Lessons from the Ebola Virus

The importance of hand hygiene in dental practices

The Ebola epidemic in West Africa became international news in March 2014 with the first confirmed case of what would soon become the worst outbreak of the disease since its discovery in 1976. At first the world took little notice of people affected by a disease few had even heard of, but within months the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the outbreak to be an international health emergency, and as the infection spread rapidly, the world was made to sit up and take notice.

Thankfully, in January 2016 WHO finally declared Liberia’s Ebola epidemic to be over, joining the status of Guinea and Sierra Leone to effectively bring this terrible outbreak of the disease to an end. But how did this outbreak happen, and what has it taught us in relation to infection control?

What is Ebola?

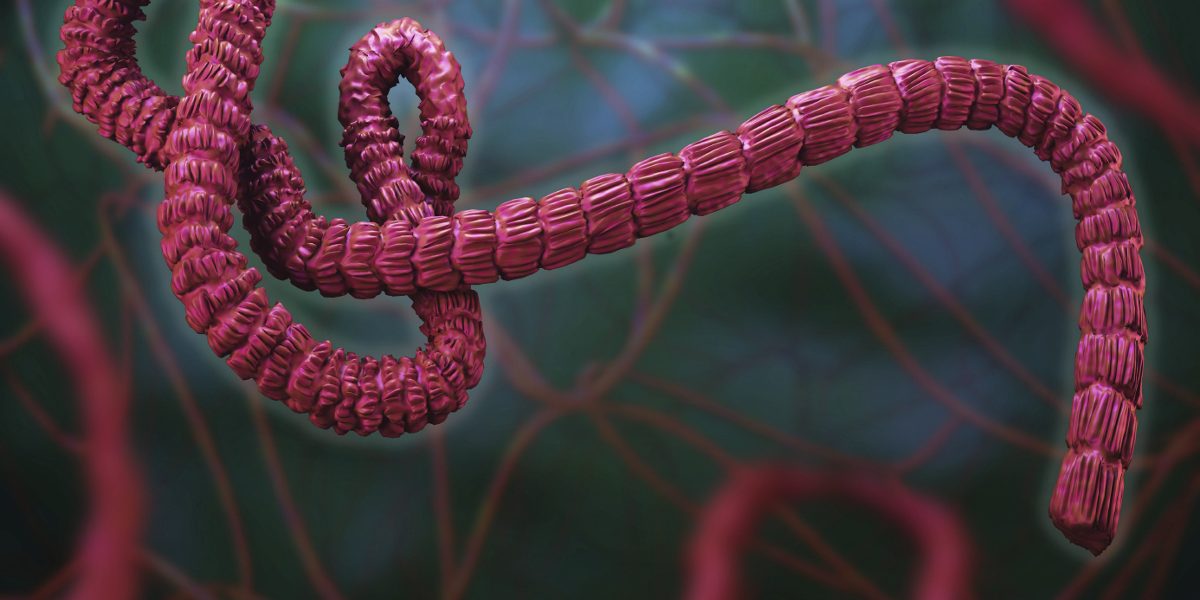

Ebola is a viral illness of which initial symptoms can include sudden fever, intense weakness, severe muscle pain and a sore throat. The alarming latter stages include vomiting, diarrhoea and, in many cases, both internal and external bleeding. Ebola, just like other more common blood-borne viruses such as HIV, Hepatitis B and Hepatitis C, is spread between humans by direct contact with infected blood, bodily fluids, or indirectly through contact with contaminated environments.

A virus is an infective agent, smaller than a bacterium, which is able to multiply only within the living cells of a host. The Ebola virus fuses with cells lining the respiratory tract, eyes or body cavities where the virus’s generic contents are released into the cell. This genetic material then uses the cell’s mechanisms to replicate itself, producing new copies of the virus that are released back into the host’s system with major consequences.

The spread

With no vaccines or drugs available to combat Ebola and with infection spreading, medical experts had to work fast to break the chain of infection. This posed a problem for many in West Africa where traditions around religion and death involve close physical contact, including the ritual preparation of bodies for burial involving washing, touching and kissing; traditions that were extremely hard to break.

However, perseverance eventually paid off as medical teams worked tirelessly not only to save thousands of lives, but also to educate the local population about how Ebola is contracted, how to prevent its spread by avoiding contact with infected people and environments, and how just simply washing hands and improving hygiene were all ways to combat the virus.

Principles of infection control

The threat from Ebola may not at first appear to have a lot do with dentistry, but the underlying principles of infection control that eventually halted this outbreak are exactly the same as used daily in any dental surgery. Fundamentally, it is about breaking one or more links in the chain of infection and preventing the infectious agent – in this case, a virus, spreading to a new host.

The risk of Ebola transmission in the UK remains very low and the environmental conditions here are very different from those found in West Africa. However, it has been a wake-up call to the dental profession about how easily members of the dental team can come into direct contact with pathogens, especially those found in blood and saliva, and that any patient visiting a dental surgery could potentially be carrying an undiagnosed infection or be at risk of acquiring an infection if stringent hygiene standards are not maintained.

Diseases can be transmitted from the patient to staff, from staff to the patient, or from one patient to another. Those in contact with any patient should always wear standard PPE such as disposable gloves, masks, eye protection and plastic aprons, especially during surgical procedures. Hand hygiene is paramount and hands should be thoroughly washed, preferably using proven bactericidal hand cleansers rather than just soap and water, before and after every patient is seen.

All surfaces and items of equipment within the treatment area need to be cleaned and disinfected prior to the next patient being seated, using all-in-one surface cleaning and disinfecting wipes or solutions that are alcohol-free. As stated in HTM 01-05 6.57: “If there is obvious blood contamination, the presence of protein will compromise the efficacy of alcohol-based wipes. NOTE: Alcohol has been shown to bind blood and protein to stainless steel. The use of alcohol with dental instruments should therefore be avoided”.

It is recommended that all work surfaces should be cleaned with a wide spectrum, microbiocidal wipe or spray that have proven efficacy against mycobacteria, fungi, yeast and enveloped viruses such as HIV, HBV, HCV, H1N1, H5N1 and TB. When used on medical device surfaces, these cleaning and disinfection products should also conform to the requirements of the Medical Device Directive 93/42/EEC.

Prevention is the cure

The Ebola outbreak put a spotlight on how easily disease can spread, and ultimately how it can be prevented using infection control procedures including PPE and teaching people the importance of hand hygiene and clean environments. For the dental team ensuring rigorous implementation of infection control protocol drastically reduces the likelihood of contacting any infection in the dental surgery. Understanding how to break the chain of infection and how pathogens are transmitted makes it far easier to take the correct measures against them.